Together

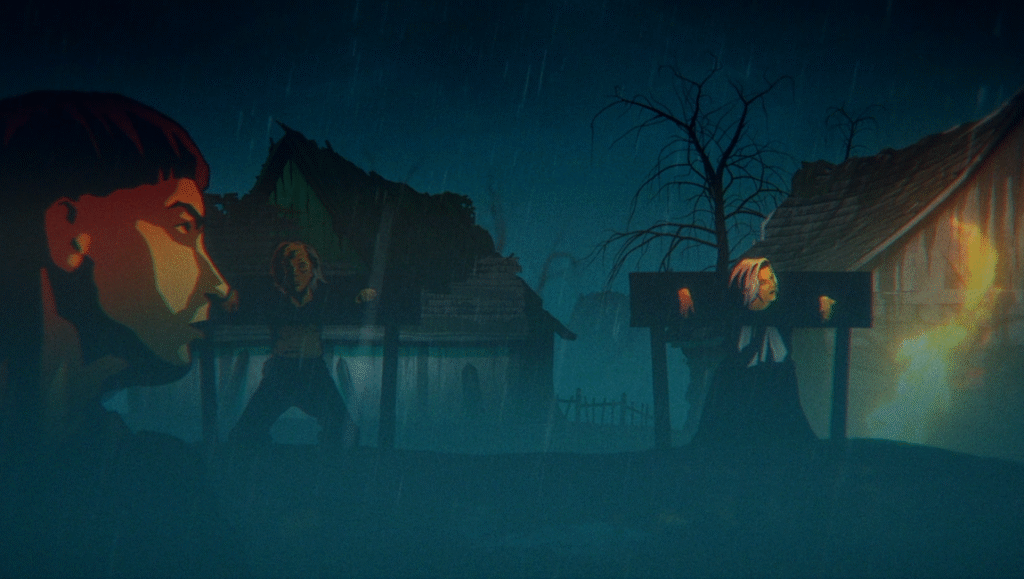

In Michael Shanks’ body-horror-comedy Together, the recently-engaged but longtime-dating couple of Millie and Tim (played by real-life spouses and frequent creative collaborators Alison Brie and Dave Franco) find themselves stranded in a mysterious, underground chamber after being caught in the rain while hiking in the woods. The chamber, which looks as though it’s taken decorating tips from the Bhutanese cave at the beginning of The Empty Man, has a murky pool of water at its center, and after Tim drinks from it (ignoring Millie’s concerns), he finds himself forcefully drawn to the woman he’d previously demonstrated reluctance to commit to. As in literally. When they awake, still on the floor of the chamber, Tim finds a sticky film has developed on his leg, effectively functioning as industrial-grade super glue, briefly adhering his skin to Millie’s. And things don’t exactly get better once he violently rips himself free of her and they climb free, returning home. Despite claiming, in a heated exchange, that he feels like a prisoner in their own home with no real sense of identity or autonomy in the relationship, Tim develops an uncontrollable physical compulsion to be near his new fiancée, which manifests itself in some alarming ways: things like being guided, as if by an invisible hand, to be close to her even when she’s at work, or how, when he’s asleep, he unwittingly sucks the hair from her head down his throat (it all a bit like the psychic bond between E.T. and Elliott, only with less whimsy). The one-time commitment phobe has been struck by an insidious case of codependency; he’s being tormented by a metaphor.

What Together is doing here isn’t exactly subtle, although in fairness to Shanks and the film, it’s hard to say that subtlety was ever the objective. Early scenes are larded with dialogue solely for the benefit of the audience that paints a portrait of an atrophying relationship. Gigging musician Tim has long dreamed of being a rockstar, but, now 35, his “taking the plunge” and moving upstate with Millie seems to be an acknowledgement that his career is going nowhere and he’s clinging to her as a lifeline (she at least has the stability of being an in-demand grade school teacher). We’re told that the couple haven’t had sex in forever, with Millie falling into a practiced habit of propositioning Tim and anticipating him politely rebuffing her with some variation on how tired he is and saying “maybe tomorrow.” The film gradually doles out a traumatic backstory for Tim that dovetails with the themes of the film while also explaining his recent disinterest in intimacy, but the routines and rhythms may strike a nerve with anyone who’s been in a relationship that’s shifted into a gear where you start to feel more like roommates than lovers. Even that recent engagement comes with a rather damning asterisk: tired of waiting for Tim to take the lead after all this time, Millie instead proposes to him in front of all their friends at their going-away party, and he’s so dumbstruck (either by the inversion of traditional gender roles or that he’d never contemplated marrying her) that he leaves her hanging, still on bended knee, for a small eternity before eventually mumbling “yes.”

Body-horror is a rather pliable subgenre when it comes to social commentary — one need only look back to last year’s Best Picture-nominated The Substance to identify a recent example that permeated the zeitgeist — and Shanks has devised a skin-crawling (literally) scenario to explore fears of losing one’s individualism and, indeed, the entire sense of the self by committing to another person, which is represented here as two bodies physically merging together. At first, Millie is relegated to a concerned maternal surrogate. She tends to Tim’s emotional and physical wounds while becoming increasingly exasperated by his newfound clinginess, which even lends the film a Freudian bent as Tim desires, on the most primal of levels, to be physically inside of her. However, after an impromptu, rather painful, tryst in a school toilet, the sickness passes to Millie as well, and soon they’re functioning almost as living magnets. Tim and Millie’s attempts to quarantine one another at opposite ends of the house fail as their bodies override their willpower, contorting themselves into inhuman permutations (accompanied by considerable “cracking and snapping” foley effects), dragging them by their fingertips toward one another before bloodlessly grafting their arms together. Needless to say, separating from one another in the morning isn’t quite so bloodless, as it requires several belts of whiskey, muscle relaxers, and a Sawzall (it should be addressed that while the electric saw moment is prominently featured in the film’s marketing, gorehounds will probably be disappointed with how much is elided in the sequence, presumably as a budgetary concession).

For all of the DIY surgery and rubbery conjoined prosthetics — there’s a subplot in the film about a couple of missing hikers with echoes of our main characters which belatedly provides the requisite, creature-feature jump scare — what’s likely to be triggering for some viewers is how it presents the fairly commonplace ebbs and flows (and the anxieties that come with them) of cohabitation and fidelity as something abnormal. In the film, sharing your life with someone and sacrificing some amount of personal freedom to do it is literally akin to an alien presence invading the body and robbing one of their self-governance and even personhood. Sounds hyperbolic, sure, but, then, there’s a reason even many happy couples keep separate checking accounts and bathrooms. The film seems to be cheekily arguing that you can only go so far as two individuals and that true equilibrium can only be achieved when you tear down the barriers you put up between yourself and your partner and embrace functioning as a single cohesive unit. Essentially, learn to stop worrying and love combining your record collections and quiet nights at home watching the same junky reality shows.

Together is so message-first in its approach there’s never any shortage of symbolism to note as everything tends to be laid directly on the surface. It’s the sort of film where characters quote Plato in everyday conversation simply so we can get an ominous callback to it later on, or it sets up its tongue-in-cheek climatic needle drop so far in advance that you’re going to kick yourself when you finally hear it. However, it’s somewhat more academic qualities threaten to stifle its effectiveness as a genre film. Together has its squeamish moments, but it’s not particularly thrilling on the whole, and everything other than the Brie-Franco dynamic (both actors admirably commit to the punishing pratfalls required of the scenario) feels rather anemic by comparison. The film can’t decide whether the mythology of the chamber — we’re eventually told it was once a “new age” chapel that collapsed into the ground — is entirely irrelevant or hugely consequential, which leads to late exposition dumps — including the old standby of the incriminating home video playing on the off chance one of our heroes wanders into what is ostensibly an empty house — from the secondary antagonist hiding in plain sight who delivers off-brand Clive Barker lines like “the ultimate intimacy in divine flesh.” Even more frustrating, the film seems to be working backwards from the revelation in its final shot; waving off both the psychological implications — which feels very much the point of the entire film — as well as the practical realities for a cute “gotcha.” Together wants you to think very much about what this all means but, at the same time, not very deeply about it. — ANDREW DIGNAN

Terrestrial

As Terrestrial opens, we meet Allen (Jermaine Fowler), a successful sci-fi writer who is of late enjoying a massive career upswing as his work has seemingly net him a fortune, with his next project already tapped to be produced into a major feature film adaptation. To celebrate his accomplishments, he invites college friends Maddie (Pauline Chalamet, sister of Timothée and of The Sex Lives of College Girls fame), Ryan (James Morosini), and Vic (Edy Modica) to stay over at his Hollywood mansion, enjoying a relaxed weekend of casual merriment and revelry. Inspired by a series of novels known as The Neptune Cycle, penned by Allen’s literary hero S.J. Purcell (Brendan Hunt), Allen shares news of an alien encounter he had with his friends, which is what has inspired him to write his next novel. Though supportive of their friend, the trio can’t help but feel that something is off about Allen’s behavior, with their host frequently stepping away for unknown activities and displaying erratic mood swings. As the getaway weekend carries on, nothing is revealed to be as it seems, with the proceedings eventually taking a darker, more unexpected turn.

Director Steve Pink, boasting quite the diverse filmography, has engaged more lightheartedly with sci-fi trappings in past projects, most notably in Hot Tub Time Machine (good for a laugh at least) and its sequel (not so good for a laugh). Working from a script courtesy of Connor Diedrich and Samuel Johnson, Terrestrial definitely hints at something otherworldly, with a potential close encounter hanging out on the narrative’s fringes, allowing Allen to put his creativity to good use. But as the title slyly suggests, Terrestrial is actually a much more grounded affair at its core, blending science fiction, comedy, and even horror, all while it takes care to stay close to the humans at the film’s center. For Allen, the reunion is a time of celebration, hoping his friends will see his newfound success and that this will help overshadow any of his past doubts or failures as a writer. Allen is an excitable man, but perhaps one with a too unhealthy an infatuation on esteemed writer Purcell, even dedicating an entire room in his mansion to all things The Neptune Cycle (a television set airs reruns of the show on a loop, featuring cameos by Hot Tub alums Rob Corddry and Craig Robinson). For Maddie, Ryan, and Vic, they’re just thrilled to spend time in such a gorgeous estate, which means they’re arguably slower to admit something is off about their friend and his fast-tracked achievements than they should be.

If this vaguish accounting hasn’t already made it clear, Terrestrial is a very difficult film to summarize to any meaningful degree, as revealing any of the film’s many secrets would spoil all the fun present therein. Without giving too much away, there’s a hard turn at the end of act one that shifts focus to another major character and places all the film’s preceding events into new perspective. Pink successfully juggles multiple tones as the weekend stay grows much darker from this point, even wading into material regarding the dangers of toxic fandom and para-social relationships. At a point, this surfeit all threatens to crumble under its own weight, but Terrestrial keeps things intact by committing to a lightness of foot, moving briskly through any potential danger zone so as to not any one thing saddle proceedings. The cast is especially helpful in service of the film’s aims, and Fowler in particular, as the actor is tasked with a very difficult role that must be played at multiple registers, which he executes impressively as he carries the film across the finish line. Ultimately, then, Terrestrial proves to be a solidly entertaining genre sandbox, a film savvy enough to undercut its weaknesses of overinflation, and one that will certainly play better to viewers who go in as blind as possible. — JAKE TROPILA

Rewrite

Attention: this one’s for all the Obayashi heads out there. Daigo Matsui’s Rewrite begins in a place we know well: a high school girl named Miyuki learns that the new transfer student (Yasuhiko) is actually a time traveler from 300 years into the future. The two of them, bonding over this secret, spend a magical 20 days together before he must inevitably return to his own time. Before he goes, she learns (after briefly visiting herself in 10 years time) that she will write a book about their time together, and that the boy will someday read this book and that will inspire his journey. All she has to do is write the book and in 10 years time, the time loop will be perfect. And so she does, and when the inevitable day arrives… nothing happens. This snippet of plot accounts for the first 20 minutes of Rewrite, the rest of the film follows Miyuki as she attempts to understand what happened (or didn’t happen) and why.

Rewrite‘s central scenario is obviously inspired by The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, a novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui from 1967 which was famously adapted into film by Nobuhiko Obayashi in 1983. The source material has spawned a number of other adaptations since, on both television, stage, and film, including a celebrated anime by Mamoru Hosada (which is actually a sequel to the original story, though it follows basically the same structure), but Rewrite seems most inspired by Obayashi’s interpretation. The title of the book Miyuki writes is Girl Leaps Time; the film is set in Obayashi’s hometown of Onomichi, the setting for a number of his greatest movies, including The Girl Who Leapt through Time (which is as much a showcase for his beloved home as it is a sci-fi teen romance); there are multiple references to the air around the time-traveler being filled with a faint scent of lavender, a running motif of Obayashi’s adaptation.

But more than mere homage, the complications of the time loop that Matsui and screenwriter Makoto Ueda (the modern master of time travel narratives behind Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes and River, here adapting a novel by Haruka Hôjô) spin go far beyond simple sci-fi mechanics into questioning the very idea of authorship, both of novels and films (and film adaptations of novels and other films), and of our own memories. It would spoil too much to go into many details at this point, so it’ll have to suffice it to say that every twist and turn of Rewrite are a delight to engage with, opening up new ways to understand not just the facts of the film’s world, but what it means to live in a reality mediated by stories that can change and disappear and remake (ahem, rewrite) themselves with or without our knowledge. For as much as Matsui locks us down in space, the Onomichi of our memory of another person’s story, he also sets us adrift in time: not between possible futures or alternate presents, but into a past that contains as many possibilities as there are people to experience it. — SEAN GILMAN

Dog of God

It’s not surprising that Fantasia organizers for the festival’s 2025 edition couldn’t help but highlight how Dog of God follows last year’s triumph of Flow, Gints Zilbalodis’ animated film from Latvia about a cat displaced by natural disaster, which became the first film from that country to ever be nominated for, let alone win, an Oscar. The comparison is so apt not only due to the films’ national origin, but because Dog of God is, in some ways, the complete opposite of Flow — it is provocative, vulgar, violent, grotesque, horny, and disturbing, in contrast to all the ways that Flow was delightful, gentle, and warm. (Dog of God’s cat, likewise, gets up to some activities that are the furthest thing away from Flow, and we’ll leave it at that). It’s an easy enough selling point: Latvian animation is having a moment, so let us show you its seedy underbelly.

Dog of God, directed by the brothers Lauris and Raitis Abele, takes place in the 17th century, a time of witch trials, religious fanaticism, rampant drunkenness, and low levels of hygiene. It’s a Baltic folk horror film that adds regional specificity to legends of lycanthropy and alchemic magic, and it largely succeeds due to this attention to detail, alongside the often gorgeous (if appropriately grimy) rotoscoped animation. Whether a sacred strand of straw, ostensibly taken from baby Jesus’ manger, is stolen, or a werewolf is arising from Hell through the dirt, or an ostentatious local baron is going hog-wild with his wife after drinking a potion that cures his impotence, the film does its best to make and leave an impression.

In that regard, many memorable images surely do arrive, including plenty of penises, but the film ultimately ends up buckling under its limited sense of storytelling. Subplots and particular moments of both drama and comedy that ought to land with emphasis instead feel scattershot, and there’s an overreliance on the film’s pounding electronic score (courtesy of co-director Lauris) to make up the slack. It’s an admittedly effective strategy on the surface, but it risks drowning out the story and its emotional weight, and it ‘s not nearly enough to suture together a holistic experience. In other words, there’s the feeling that the filmmakers, perhaps understandably, are indulging every extreme, narratively and stylistically, they can to grab the viewer’s attention, but it has somewhat overbearing consequences. Tougher to counter is that it’s always a treat to see such an energetic mixture of aesthetic ambition, juvenile humor, and historical distinction, particularly in animated film. But even at just 94 minutes, Dog of God undeniably overstays its welcome, and plenty of viewers are likely to leave feeling a little exhausted. Then again, perhaps that’s the point. — JAKE PITRE

Honeko Akabane’s Bodyguards

A young man named Ibuki (played by multi-hyphenate star Raul), styled as a “bad boy” because of, presumably, his dyed-blonde hair and dangling earrings, is recruited by the mysterious head of a Japanese CIA-like organization to protect his high school-aged daughter Honeko (model-turned actress Natsuki Deguchi), who has been targeted for assassination by every criminal organization in the country. She also happens to be Ibuki’s childhood friend. The hitch is that she doesn’t know anything about her real father (she was given up for adoption) and can’t know that she’s being protected or that people are trying to kill her. The other hitch is that every other kid in her class is also a bodyguard trained to protect her.

This is the irresistible starting point Honeko Akabane’s Bodyguards, director Junichi Ishikawa’s adaptation of Nigatsu Masamitsu’s manga of the same name, which offers a sturdy structure for serialized storytelling (every new gang attack leading to a new story arc, while the audience gets to know the two dozen or so bodyguards; and the inevitable fitful romance between Ibuki and Honeko sees its inevitable ups and downs — one could easily envision this as a 50-episode anime series) condensed down to two hours. Ishikawa, a 20-year veteran of television (both series and movies) as well as film, does a fine job of capturing the energy of a serial, though he is inevitably limited by the running time. We get to know few of the characters outside the two leads, and even they are reliant on genre code signifiers more than establishing unique personalities. Ibuki’s bad boy image is quickly dispensed with as he realizes he’s in way over his head, both with the other bodyguards (who are all more experienced than him) and Honeko (who really doesn’t have much of a personality beyond being a nice kid who happens to be the Cutest Girl in the World). But the film is bursting with energy, rushing from one story to the next with only a few moments to spare for the heartbreaks and frustrations of teen romance.

Most of Honeko Akabane’s Bodyguards‘ fun comes with the discovery of the other bodyguards, all of whom are introduced with comic book-style splash pages announcing their names and specialties. There’s a karate girl, a ninja, a master of disguise, a hacker, a girl who’s really into torturing people, an engineer who pilots a robotic mascot suit — you know, typical high school stereotypes. This cadre is lead by a master strategist, played by Daiken Okudaira, who recently popped up as the surprisingly capable assistant in Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cloud. The interplay between the kids also provides a whole lot of fun, and the high school relationship tropes played more or less straight effectively balance the gleeful anarchy of the film’s fight sequences.

Cinema has delivered a lot of oddball action comedies in the last few years, but few have been able to pull off the the mix found here between fun fights and quirkiness without either compromising the choreography of the action or overplaying the cutesy goofiness until the point of simply being annoying. Your mileage may vary on that kind of thing, of course (there are, for example, some benighted souls out there who find the Baby Assassins insufferable — we must pity them), but Honeko Akabane’s Bodyguards finds a breezy middle ground, never as edgy or truly weird as, say, Takashi Miike’s Ace Attorney, but mercifully a whole lot more tolerable than the Kitty the Killers or Gunpowder Milkshakes of the world. — SEAN GILMAN

Comments are closed.