Nightmare’s Advice

Renaud Després-Larose and Ana Tapia Rousiouk, along with their frequent collaborator Olivier Godin, represent an alternative stream of Quebecois cinema, one that is both shoestring and grandiose, and that flits between extreme doses of whimsy and self-involved seriousness. The duo’s work is at least partially fueled by French cinephilia, but this passion is filtered through an academic need to cite, defend, and categorize even the most inconsequential idea, even as this deliberate processing of experience stagnates and runs in tension with an artistic project that aspires toward a sense of formal and character-driven freedom.

The first section of Nightmare’s Advice is, in contrast to what follows, a pure game of mystery. Lucie (Marie Ève Loyez) is a grad student whose PhD funding is running out. She shares an apartment with an older woman who imposes strict rules on her comings and goings, and seems to have no friends. Her routines involve a lot of travel time on her moped, and by foot when she occasionally disappears into the woods. Hypnagogic cinema is often used as an embrace of psychological effects in genre films, but here this state is achieved through theatrical blocking and an absence of context. We don’t know whether we are seeing dreams, memories, Lucie’s typical excursions, or the nightmare of the title. (Like Després-Larose and Rousiouk’s first feature, The Dream and the Radio, their camera sensor’s murky detection of low-level light and nightfall is put to constant use as an obscuring effect.) The most unsettling aspect of these scenes might be their total acceptance of chance, with characters entering the frame or hiding within it to little acknowledgement from Lucie or the camera; perhaps this is normal behavior in Montreal, or maybe there is something half-imagined about these briefly-glimpsed figures.

The film’s early rupture from this mode undoes any potential confusion and clarifies its intentions. Lucie is said to be a sleepwalker. It turns out that the thesis she has stalled completing is about “play,” and she has experienced a total onset of anxiety that she is simply not a natural enough participant in any playful attitude to be the rightful author of such a text. Even her conceptual approach is compromised, as she has been forced to choose between strict disciplines: either critical anthropology or phenomenology, each with their drawbacks. The filmmakers’ way into this intractable problem involves an extended, belaboured homage to Jacques Rivette, particularly his Céline and Julie Go Boating. There is something novel in this, perhaps, if only because Rivette is a perpetually neglected figure next to the dozens of independent acolytes that have taken up Godard, Rohmer, or their Left Bank contemporaries Varda, Resnais, and Marker as models. So incorporating dance and clowning, and pairing two women together as investigators with transferrable personalities, is a clear and somewhat unusual way of reinterpreting Rivette outside of his Parisian context.

Accordingly, Lucie meets her kindred spirit Béatrice (Geneviève Ackerman), and is changed by the encounter. But the plot is no political and psychogeographical conspiracy; she’s stuck between two bad romantic options: a failed actor and her thesis advisor. We never see these romantic developments; they are exhibited as autopsies of mostly-dead connections. In all this, Béatrice exists as little more than a sounding board for long, digressive monologues, and has no problems of her own; she is basically imaginary, and the film always comes back to Lucie’s academic writing block and emotional degradation.

Like Rivette, the film does invoke magic, myth, and ritual, but only in a cursory, unsubstantiated way. It’s not just that “Athena’s helmet” is only a name for a costume piece, and that the duo’s most transformative act is a bonfire — hardly an unusual activity for post-grads in Montreal. It’s that Rivette’s purpose, across films both more and less successful, stemmed from a total vision of how play becomes a different way of understanding and crossing public space in a city full of ghosts. There’s no way that Després-Larose and Rousiouk aren’t aware of this idea, but their film is so obsessed with its minor concerns that it ends by collapsing into a black-box theatre soliloquy, in which Lucie laments her uneventful flings. While Rousiouk’s collagist approach to the film’s music is complex — classical and modernist compositions vie for space — it often functions as a wall of sound. Després-Larose’s cinematography is similarly “active” without finding the kind of mysteriously affecting and disorienting images necessary, perhaps, to carry off the film’s conceit. This problem of superfluous detail and over-explanation is perhaps more than anything a model of frustration. Obviously, the duo’s films are pointedly small and depopulated partly by choice and partly by contingency. And the model is also chosen because it keeps their production within a trusted circle.

This scale could be what makes their spirit of improvisation possible at all. But it’s also what keeps their improv-as-action from feeling fully considered or effective. “You’re playing with boundaries,” one character says in the film. As a matter of academic description, this is accurate; the boundaries of relationships and art practices and studies identified in the film are sketched out to leave an uncannily detailed resonance for a contemporary like-minded audience. But it’s telling that the film relinquishes the power of its opening stretch, in which little is stated outright, and the slippage of boundaries — still clearly situated within a hyper-specific milieu — is left open, unexplained, and powerfully felt. — MICHAEL SCOULAR

Tycoon

Charlotte Zhang’s docu-fiction of contemporary and prospective Los Angeles, Tycoon, contends with events both real and imagined, intimate and global. In it we follow Lito and Jay (Miguel Padilla-Juarez and Jon Lawrence Reyes), two grifters always hunting for their next score. Theirs is a story of conspiracy and care, hoisted up and shattered just like Los Angeles, which, in Zhang’s imagination, is a city of pent-up rage and political corruption thanks to a devastating livestock crisis in the lead up to the 2028 Olympics. In this way, Tycoon is reminiscent of Gary Indiana’s truish-crime novel, “Resentment.” Surveying every strata of Los Angeles society, from criminal underworlds to the cultural establishment, it alights upon the same details and observations as Tycoon: the desperate among us gamble big, the biggest among us consolidate power, and the rest scurry about like cockroaches trying to make sense of it all. Told in conjunction, these parallel stories of grifting run amok reveal Zhang as an astute synthesizer of the moment, whose relative youth neither overstates her anger nor undercuts her analysis.

Adapting to change is hard, especially for stubborn young men like Jay and Miguel. The opening scene elucidates how the general listlessness with which they move through their lives competes with their active imaginations. Parked in an empty lot, they munch drab vegan fare, the only food available to them in a post-meat society. Zhang renders their meal in an effectively miserable light. Miguel sniffs suspiciously at a falafel, and Jay throws away his pre-packaged tub of brussel sprouts, which scatter onto the concrete in a pathetic arc of green and yellow. In the distance Jay points out a camera-equipped streetlight in the distance that he says emits a mind-controlling frequency undetectable to adults. Jay mumbles his way through a half-baked explanation of the technology, cracked, but lucid enough to keep our attention. But Miguel isn’t convinced. The scene finishes with the boys no closer to, but no further away from, consensus; the circular trajectory of their conversation befits the moment in which they’re mired — entrenched, halting, empty.

When they’re in hustle mode, Miguel and Jay scuttle around the city like cockroaches, searching for a new way to exploit the large-scale corruption wreaking havoc on Los Angeles. One night they boost a shipment of insect protein supplements from Ootheca Inc., a new mega corporation that has spawned opportunistically, and to lucrative ends, from the ongoing livestock crisis. Miguel and Jay aren’t underground political operatives engaging in direct action, nor are they mere hoodlums looking to wreak some havoc of their own. Instead, Zhang’s documentary-like visual style reads between the lines, and in Miguel and Jay we see two young people trying to strike an appropriate, or at least sustainable, balance between concern for the world-at-large and for their immediate futures.

Miguel, however, quiet and introspective, isn’t so sure how sustainable his and Jay’s criminal exploits can be. How many cars can they boost, how many shipments can they hijack and scalp on Instagram, before their luck runs out? Jay isn’t nearly as concerned — in fact, he thrives in that crack between the certainty of danger and slim chance of success. Besides, his new girlfriend’s dad is worth $5 billion, and soon he’s moving with her to Amsterdam. This modern Barry Lyndon is just along for the ride. Zhang is alert to the conventions of drama enough to leave ample room for contrast. The care with which Jay regards the subtle fade along Miguel’s temples as he gives him a haircut one afternoon, and the care with which Zhang regards them both, fortifies, if just for a moment, a Los Angeles that seems at all times to be crumbling around them. That care is the film’s unspoken strength. One senses, too, that it’s kept Miguel and Jay together through even greater conflict, likely in spite of the self-preservationist impulses that later drive them apart.

Tycoon wears its DIY bona fides on its sleeve. Shot over weekends on various filmmaking apparatus (mini-DV, iPhone, Super-8, night vision), its improvisatory, patchwork construction hints at the vibrancy of its makers’ own lives. Zhang weaves sequences of the real world into her imagined one, the kinds of events you imagine the crew captured during their own downtime or on the way from one location to another, like impromptu drifting exhibitions in empty intersections, or the jubilant celebrations over the Dodgers’ World Series victory. Others capture the past, but bear jolts as contemporaneous as anything else in the film, like the 1992 uprisings, the 1987’s Operation Hammer, and other violent, militarized crackdowns before the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. The feeling they inspire isn’t one of gawking detachment — though, at one point producer Kenneth Andrew Sarmiento Yuen stares awestruck at those ecstatic baseball fans — but of admiration. Participant, observer, or interpolator: everyone has a part to play in this saga. — CHRIS CASSINGHAM

Phra Ruang: Rise of the Empire

Among all the defenses for art (as if art ever needed defending), the “timeless and universal” argument has the biggest currency. In this argument, human nature and emotions are constant regardless of the differences in societies, cultures, and histories, and the art which captures the essential emotional core while adapting the aesthetic of its environment is the most valued. Approaches to emotions might change, but the emotion remains the same. This concept, despite being prevalent across all the art forms, appears to be the most abused in cinema because of its sheer ubiquity and mass reproducibility in our economy of images. The world-weary fatalism of noir, for instance, itself a cinephilic conjuration, is an aspirational emotional mode for filmmakers born even after the ‘50s, with aesthetic and environmental questions serving as mere molds to shape this mood into the film’s structure.

Though one could understand where this argument is coming from, as our ability to empathize does allow us to bridge works across eras and cultures, there’s always the danger of smoothing out specificity for universality. The limitations of this argument are especially pronounced when we look at emotions arising exclusively from particular societies (information overload in our times, for instance), or when we approach the past to understand our present, like Chartchai Ketnust, in his film Phra Ruang: Rise of Empire (premiering outside Thailand at IFFR). Taking on a rather charged figure whose mythic narrative almost forms one of the nationalistic myths in modern-day Thailand, Phra Ruang follows the journey of the legendary eponymous ruler’s sons, the younger but worldly-wise Khun Bang (Thanavate Siriwattanagul), and the older and belligerent Phraya Pha Mueang (Pongsakorn Mettarikanon), who must put their differences aside to reclaim the “Thai kingdom” from the devious “Khmer” nobleman Khom Sabad Khon Lampong. Ketnust, however, complicates this narrative by deliberately foregrounding the period he’s approaching the myths from. The colorful, mythic past is tugged by the rather drab, black-and-white present, as a theatre troupe reimagines a 20th-century shadow play describing the consolidation of the Thai kingdom.

Auditioners for the play question the propagandistic nature of the source text, but the theatre director (Pongsakorn Mettarikanon again), dismisses their questions with the usual hackneyed drivel of telling it as it is without any nationalistic sentiments. At first, it appears that Ketnust confirms their sentiments, going for the coveted universality with minor differences. Phra Ruang reaches for the mythos of epic storytelling by retaining the plot of the text, but does so with elements more familiar to modern audiences. The theatre director asks his actors to imagine the past, snaps his fingers, and the film dutifully switches. Music is injected to inspire awe in many of the period sequences, but instead of employing “traditional” Thai music that is deemed respectable for historical dramas, Phra Ruang’s score features a rather unique blend of Thai Pop, prog rock. and metal, with the occasional intrusion of non-Western instruments. The mechanics of adaptation initially come across as an elegant hand-holding strategy asking the audience not to shy away from a period unknown to them, and Ketsnut is unafraid to inter-cut between the “re-imagination” and theatrical process. Martial arts glides in the past are shown to be meticulously mounted sets in present, and this self-reflexivity doesn’t deflate the myth but only adds to its majesty, with Ketnust’s theatrical constructions as elegantly orchestrated as his battles and martial-arts bouts.

Adaptation here appears as a modernist method to reinforce the allure of timeless texts, but Ketsnut slowly problematizes the nationalistic mythopoesis. Events in modern life start mimicking the events of the play, with the actors becoming entangled with their respective pair in the play. The stirrings of romance themselves emerge from the colored lenses of the mythic past, where even fond memories are inextricably intertwined with scenes from the Phra Ruang story. A yearning for the myths of a shrouded past clouds the actions of all the characters, until the differences start catching up to them. The theatre director even, rather unexpectedly, questions the resemblance of early Buddha statues to the Buddha. The past can only be apprehended through found objects and texts, all of which are projected as myth through the lens of our anxieties and longings. Phra Ruang frankly admits the impossibility of deciphering any truth, so, like its predecessors, it strives for the realization of a mythic ideal. In doing so, Ketnust does diminish the radicality of his questions, but not without introducing frictions between his various layers that remind us how appeals to universality in art can be easily assimilated into nationalistic and even fascistic myths, leaving behind mildly disaffected citizens at best disappointed with reality not living up to the impossible, yet simplistic, dream. — ANAND SUDHA

Tunnels: Sun in the Dark

Tunnels: Sun in the Dark is a rarity in the West: a film about the Vietnam War told entirely from the perspective of the Viet Cong. Of course, it’s much less rare in Vietnam, but Vietnamese films almost never make it to our shores. And when they do, they usually star Veronica Ngô. Tunnels might be read as a propaganda movie, as it’s about the heroic resistance of the VC against the American invaders, and the longest speech in the film is a defiant one about how long the Vietnamese have struggled for freedom and how determined they are to fight and die for their cause. But if you’re sympathetic to their cause, or really just know anything at all about the Vietnam War, that’s not propaganda, it’s just spitting facts. On the contrary, a film like Tunnels lays bare exactly how almost every American film about the war is itself propaganda.

The plot is simple: essentially a reverse-angle view of Oliver Stone’s Platoon, which revolved around a lengthy American siege of a Vietnamese tunnel complex (with a detour into a My Lai-style massacre and lengthy meditations on whether Charlie Sheen should kill innocent unnamed civilians or Tom Berenger). We join a band of guerrillas as they occupy a large underground (literally) network. Their mission is to protect an intelligence communications center at the base of the tunnels, three stories down. The character types are familiar: the grizzled veteran leader in charge of too-raw recruits; the man of mystery in charge of the intelligence unit; the hotheaded young soldier too smart for their own good (in this case a woman, all-too-rare in a Western war movie but not at all in a Communist one); the stranger who joins them and who may or may not be a spy; and an array of other character types that would be just as familiar to the audiences of The Sands of Iwo Jima or They Were Expendable.

For the most part, these characters and their stories are well-drawn though, confined as they are almost entirely to action rather than melodrama. There is a bizarre subplot about a sexual assault that doesn’t make any sense, as well as perhaps the most poorly-timed sex scene since Munich. But by and large the film rolls along with classical precision: the first 45 minutes is spent introducing the characters and the geography of their world, while the last hour details their increasing desperation as the Americans close in and the people we’ve come to know meet their fates. Director Bùi Thạc Chuyên has a careful eye for spatial coherence, laying out the complex and its environs enough that we always know exactly where we are when things start getting blown to hell. And things do get bad: we get snipers and tanks and snakes and rocket launchers and floods and fire and all kinds of deadly mayhem. At times, the action even nods to something like the existential horror of the tunnels of Andrzej Wajda’s Kanal.

But Tunnels most resembles the war movies recently coming out of the PRC, films like The Battle of Lake Changjin, Snipers, The Eight Hundred, and many more that the Chinese regime feels are valorizing statements about the Party and its warriors, all of which are derided in the West as propaganda, works of concession by once great filmmakers (names like Tsui Hark and Zhang Yimou) to the power of the state. Most of the Chinese ones this writer has viewed are more complicated than their reputations, however, presented a clear-eyed view of the cost of war, not just its honors and glories. The losses in Tunnels too are deeply felt, but there’s never any question that the individual sacrifices for the collective cause will ultimately be worth it. Tunnels concludes with newsreel and documentary footage of complexes like the one depicted in the film, along with comments from the men and women who served in them. It is unabashedly proud of the Viet Cong, but does that make it propaganda?

One of the interesting things about war movies is that while they’re one of the most popular genres of propaganda, movies that governments and cultures produce to instill nationalistic virtue in their citizens, the movies themselves are basically all the same. The only real difference is the ideology expressed in the speeches the characters deliver to each other (but really to the audience). Even then, however, if you move around a few words here or there (“imperialist,” “capitalist,” “communist,” “fascist,” etc.), even those speeches are basically the same, hitting similar notes about, say, a small group of heroes standing together against a common foe, or the need to defend the homeland from the foreign invaders, or how war is hell and the bosses don’t care about the everyday soldier so the folks in the trenches have to just fight for each other.

Which is not to say that we shouldn’t ever call a particular war movie a work of propaganda. Rather, what we usually mean when we call a movie that is that the movie isn’t very good. Its exposition is clunky and preachy, or the film is racist in its depiction (or in some cases, complete erasure) of the enemy, or it isn’t sufficiently anti-war for our tastes. François Truffaut famously claimed that it was impossible to truly make an anti-war film because the cinema glamorizes everything it captures. Samuel Fuller, who should know, called Full Metal Jacket, a movie that most of us experience as a horrifying picture of both the military and the war, a recruiting poster. Relying on production money isn’t a reliable indicator of propaganda either: many countries subsidize their film industry with, more or less, supervision over the movies that get made. Some countries, like present day China, have strict, if ambiguous, rules about what can and cannot be depicted about the wars of the nation’s past. Others, like the U.S., are governed by corporate interests that are mostly aligned with the political power structure. In both cases, there are things one simply cannot do in a mainstream war picture. And in both cases, ingenious filmmakers always find ways to express meanings contrary to the system, while working within its rules. Tunnels is in no way contrary to the system, but it’s still a damn good war movie. — SEAN GILMAN

Accept Our Sincere Apologies

An unsettling drone hums underneath nearly every scene of Juja Dobrachkous’s sophomore film Accept Our Sincere Apologies, a sound signaling that even seemingly innocuous moments are edged with menace. It’s the soundtrack of a mind closing in on itself, restlessly circling within its self-imposed trap. This trap is both metaphorical and literal: the film centers on Eva (Oskar Grzelak), the general manager of an opulent Venetian hotel that, for reasons she never fully articulates, does not or cannot leave. A quasi-narrative, impressionistic rendering of an unravelling mind — a classically Gothic setup, rendered by Dobrachkous with appropriate eeriness — Accept Our Sincere Apologies is alternately mystifying and absorbing.

The hotel itself, and the manner in which it is shot, is at least as important as the oblique plot and characterizations. Dobrachkous never shows the hotel’s exterior, instead providing glimpses into rooms, corridors, and common areas, including a check-in desk that stands in front of an archaic wall of keys. Director of photography Veronica Solovyeva shoots these spaces with crisp, black-and-white digital photography. The widescreen frames can capture panoramic interiors and winding halls, yet Solovyeva often opts for tight close-ups with jittery, handheld camerawork. The hotel, then, reads as a simultaneously cavernous and cloistered space; befitting of Eva’s narrow perspective, it appears to the viewer as a sprawling maze that teems with dead ends.

Eva presents as a hypercompetent administrator, delegating tasks with brisk efficiency and managing any number of guests’ absurd complaints, yet underneath her professional exterior she is jittery at best and despondent at worst. Her voiceover overlays much of the film, mostly consisting of literary, introspective musings — “when even death turns away, what will be left for you?” — and Dubrachkous also shows Eva in a number of private, harried moments sleeping in hotel rooms that she is clearly not meant to be occupying. Eva becomes embroiled with a mysterious guest, Contessa (Krista Kosonen, the only professional actor in the cast). Contessa is an eccentric with an imaginary dog, and Eva quickly latches on to her. Contessa, though, has a checkered past that mired her in legal troubles, and it becomes clear that Eva wants Contessa to pull her out of her own psychological unmooring through ethically murky means.

The relationship between Eva and the Contessa, which develops in conjunction with Eva’s progressively deteriorating mental state, is the film’s main narrative thread, but is doled out slowly and subtly. Many important narrative elements are only gestured at, and Dobrachkous often lingers on scenes that seem to serve aesthetic or thematic purposes, aside from simple plot development. One of the film’s most notable quirks is that Eva claims to have absorbed a twin in the womb, and she has repeated visions of this twin walking, dancing, and speaking with her. The twin is played by Kacper Grzelak, Oskar’s own twin — the brothers are Polish models, and both bring a willowy, intense presence to their paired roles.

Dobrachkous sustains an impeccably oneiric, mysterious mood throughout Accept Our Sincere Apologies, bolstered by Solovyeva’s evocative cinematography, and the cast of largely nontraditional performers are fascinating both individually and collectively. Yet, like many films with an experimental bent that screen at international festivals, Dobrachkous’s film sometimes suffers from its vacillations between narrative and non-narrative techniques. Dobrachkous has given the film a conventional narrative arc that she repeatedly obscures in favor of aesthetic gestures, and as a result, the film’s internal coherence sometimes suffers. Accept Our Sincere Apologies, though, is ultimately so visually and aurally striking, and features such a distinct film-world with its liminal hotel populated by ghostly eccentrics, that the sum is ultimately more compelling than it is cryptic. — ROBERT STINNER

Fish, Fists and Ambergris

As the Hong Kong film industry has been devoured by Mainland China, drawing its stars and directors away with the promise of big budgets and even bigger audiences, a vacuum has formed in the action genre. Audiences around the world need to see stuntmen recklessly risk their bodies and lives for the sake of cheap thrills, and if Hong Kong isn’t going to provide that anymore, then we’re just going to have to go elsewhere to look for it. The 2000s saw the emergence of a Thai industry centered around Tony Jaa (Ong-Bak, The Protector), while a few years later cottage industries sprung up in Indonesia around Iko Uwais, Yayan Ruhian, and Timo Tjahjanto (The Raid, The Night Comes for Us), and Vietnam around Johnny Tri Nguyen and Veronica Ngô (Clash, The Rebel). These Southeast Asian action films revolved around remarkable stuntwork propping up familiar genre formulas, as opposed to bigger industries like Korea and India, which incorporated the flashier elements of Hong Kong style into their more established cinematic formulae and traditions.

Over the last 15 years, most of those new stars were scooped up by Hollywood or other industries: Tony Jaa’s best recent work has come in Hong Kong; Uwais, Ruhian, and Ngô, appeared in Star Wars movies; Tjahjanto’s last film was the Bob Odenkirk fight film Nobody 2; Le Van Kiet, who directed Ngo in Furie, made The Princess, starring Joey King, for Hulu, while Johnny Tri Nguyen hasn’t appeared in a film since Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods, back in 2020 (which also featured Ngô). But the industries keep rolling, even without that initial wave of stars. Just at this year’s iteration of IFFR, for instance, we’ve seen the Indonesian/Japanese hybrid Lone Samurai and the Vietnamese war film Tunnels, two of the better action films of the past year and well-deserving of a wider audience in the U.S. Fish, Fists and Ambergris joins them as an action-comedy in the Hong Kong style, with a distinctly handmade flavor.

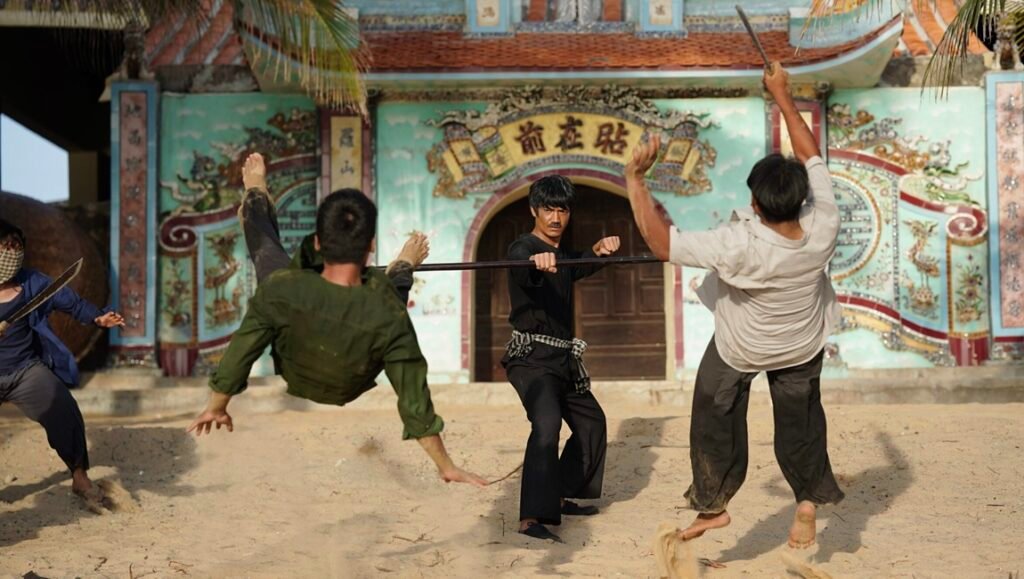

Directed by Dương Minh Chiến, Fish/Fists appears to be the debut feature of a collective of stunt performers. It concerns a small fishing village in the south of Vietnam and their statue of a whale. The whale is made of ambergris and is thought to bring luck to the villagers. Its shrine is guarded by a martial artist named Tam, played by Quang Tuấn, who also starred as the mysterious mechanic obsessed with making things explode in Tunnels. One day, his younger brother, back from Saigon for a visit, steals the idol and takes it to town in order to pay off his gambling debts, so Tam and his friend Hoang (Hoàng Tóc Dài, one of the three credited choreographers on the film, billed as “Action 3”) head into the city to get it back. There they meet a former villager turned fish saleswoman (Nguyên Thảo), and the three of them spend the rest of the film brawling with gangsters and trying to reform the prodigal brother and bring him and the idol home.

Fish/Fists boasts a simple plot with plenty of goofy humor, and its visual character is bright and colorful, even in its night scenes. In this way, it feels more like a classic HK Lunar New Year action-comedy than any movie this writer has yet seen out of Southeast Asia, where the jokes are silly, the sound effects cartoonish, and the fights as spectacular as they are almost entirely bloodless. Speaking of, said fights in Fish, Fists and Ambergris are, for the most part, variations on the trope of one or two men against an army of gangsters armed with knives and lead pipes, and the stunt crew is creative enough that these brawls never feel repetitive. Instead, they incorporate the environments — a couple of big warehouses filled with junk, but also a beach, a fish market, and a motorbike chase down narrow streets — into the choreography in unexpected ways, while also keeping the action legible at all times. The group tumults are fast and complex, incorporating a variety of martial arts styles in an agreeably hybrid version of chaotic street fighting, with a ton of extremely painful-looking stunts (to which the credit sequence blooper reel further attests). It’s no surprise that the film was a big hit in Vietnam, nor that a distributor was daring enough to release it in North American theatres at the same time as its IFFR run. Audiences would do well to seek it out. — SEAN GILMAN

Comments are closed.