Mile End Kicks

Having decided myself to migrate from a Toronto suburb to Montreal in my young adulthood shortly after hearing Visions for the first time, I am perhaps a few inches short of the requisite “critical distance” to pen a sober review of Chandler Levack’s Mile End Kicks. My notes are preoccupied with the slightest inaccuracies altogether immaterial to the success of the film — would the alt-weekly office where the lead character works feasibly have a Nathan Fielder poster in 2011? Was Mac DeMarco, name-dropped as such, not still operating under his Makeout Videotape alias that year? Would the fictional band at the film’s centre really have a Québécois nationalist playing drums?

Mile End Kicks takes for its subject Grace (Barbie Ferrara), a young female rock critic who leaves her column at an Ontarian alt-weekly for La Belle Province, where she plans to write her 33 ⅓ paean to Alanis Morrissette’s Jagged Little Pill. Fleeing the chauvinists running her Ontarian alt-weekly, led by a particularly nefarious EIC (Jay Baruchel), Grace quickly becomes enmeshed with the slightly more interesting species of male manipulators then dominating the Montreal music scene. Demonstrating these dynamics, Levack likes to situate Grace on the edge of a circle, peering over shoulders that seem to purposefully inch back into her eyeline.

Grace writes of Alanis Morrissette that “she wielded her autobiography like a weapon.” Morrissette was unabashedly Canadian and, with Jagged Little Pill, unrelentingly angry with a patriarchal music industry determined to turn her into something she wasn’t. Levack’s muse walks in a similarly autobiographical direction: the director’s first feature (2022’s I Like Movies) tackled her first job as a video store clerk, and now her second is informed by her second job as a rock critic. These regional environs are evoked with a bubbling affection that’s nevertheless vigilant about the pitfalls of nostalgia. After decamping to Montreal via Megabus, Grace moves in with her roommate (Juliette Garriépy of Red Rooms), a local DJ who is dating the aforementioned Québécois drummer (Rob Naylor), member of fictitious local legends Bone Patrol. With an acknowledged debt to Almost Famous (2000), Levack has Grace fall in lust with the band’s singer (Stanley Simons) and become the band’s de facto publicist, against the ignored-until-it-can-be-ignored-no-longer backdrop of the rest of her life falling apart.

Despite the fresh cultural victory of Cindy Lee, recent revelations about Grimes and Arcade Fire have rendered the Montreal indie moment of the early aughts difficult to regard through rose-tinted glasses (a costume choice that features in the film). This being the only feature portrait of the city in that moment — god willing, Xavier Dolan stays retired — there’s an inevitable quotient of mythologizing, but Levack is never less than clear-eyed about the foibles of Grace’s equally inevitable falling in love with Montreal. The targets are both well-worn (men who read David Foster Wallace, you’re on notice) and slightly more niche (Pere Ubu, of all bands, catches a stray). But if this can feel like Levack’s autobiographical weapon might be a bit of a foam sword, her love-hate relationship with the scene is nonetheless able to cut deep, yielding real insight into the play of toxic elements that at once attracts and repels us as (hopefully) young people.

Still writing her Toronto column, Grace inserts a long-awaited CD copy of Joanna Newsom’s Have One on Me into her work computer disk drive, having moments before been abused by her boss not, one feels, for the first time. Through tears, she types: “Strings so good they emulsify your organs.” It’s been well observed that memories of one’s twenties are inevitably tethered to the emotional tumult coloring one’s life in that decade, but perhaps never quite so directly.

Mile End Kicks goes some way toward defining a certain Barthesian myth of Montrealicity — bagels, loft parties, gender-playful indie rockers. Fortunately, the summer setting abrogates with the obligatory mention of the famed little black toques. It bears mentioning that the film is named after a shoe store located in the titular neighbourhood, one that surely induces a cringe in any self-conscious resident (think of a restaurant called “Brooklyn Style Pizza” in Williamsburg, and you’re halfway there). The most exciting and weirdest parts of the scene (The Unicorns, early Grimes) are replaced by the anodyne pop stylings of TOPS, who composed Bone Patrol’s lead single. Seeing a place so significantly entwined with my own past reduced just so, and populated with various anachronisms, I watched helplessly as, unbeknownst to myself, my own notes began to register my own shift into Grace’s eyeline, boxing her out of a circle of “true” Montrealers. But Levack’s stubbornly sober look at this myth compelled me to drop my gate-keepers key. There’s just enough venom in her sentiment, just enough affection in her takedown, to disarm the calculated coldness patrolling the limits of any scene.

Montreal is as much mine as it is Grace’s as it is Levack’s. It’s a made-up place perpetually ripe for re-definition, perpetually redrawing its boundaries as gentrification encroaches year by year. Today’s posers are tomorrow’s legends, time is a flat bagel. “Art should be hard to make,” the male manipulator-singer speaks in a vocal fry for maximum cringe. Pere Ubu might have agreed, but Levack’s art is to situate the revelations of young adulthood (“everyone is just as nervous as you” seems so simple in retrospect) in the embattled mind of the young adult living through them. We’d do well to remember that romance and disappointment were not always so clearly delineated. — CLARA CUCCARO

The Sun Rises On Us All

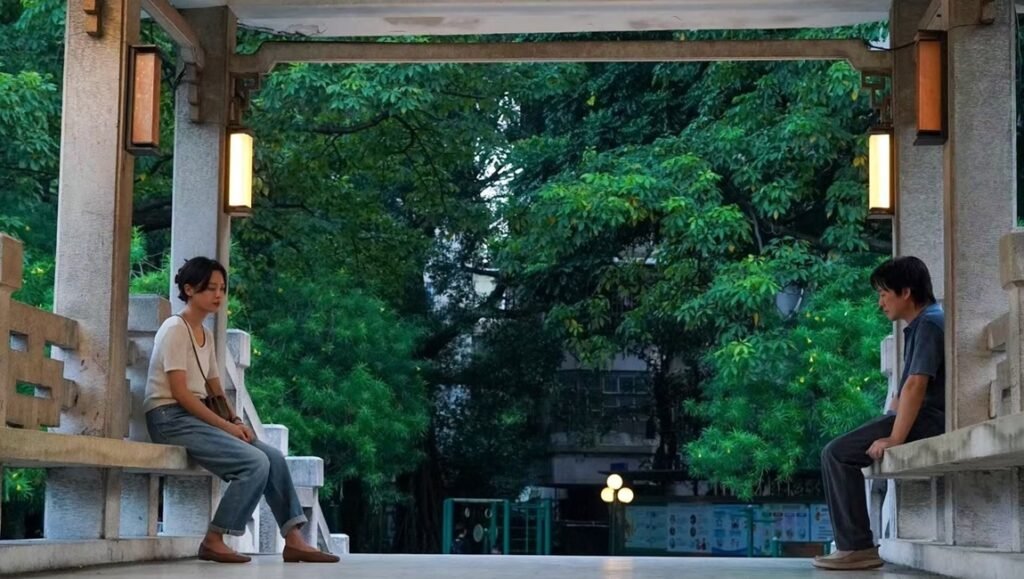

In the opening scenes of Cai Shangjun’s The Sun Rises on Us All, a woman in her mid-30s, Meiyun (Xin Zhilei), is getting an ultrasound. The technician cannot find a heartbeat, but quickly brushes Meiyun off, telling her to go to some other part of the hospital to talk to a doctor. Following this disturbing news, she returns to her boutique in the mall and starts a promotional livestream on Douyin (Chinese TikTok). She is all smiles, gazing into the ring light and holding up pastel-colored pairs of pants. But soon after, she is seen tending to a man in a hospital bed, struggling to move. We eventually learn that this is Baoshu (Zhang Songwen), Meijun’s ex-husband who is suffering from stomach cancer. Before long, Meijun is caught in a low-key showdown between her current partner Qifeng (William Feng), who happens to be married with a young child, and Baoshu. Neither man knows that Meijun is pregnant.

To its credit, The Sun Rises on Us All takes its time explaining how we got to this point. Meijun and Baoshu have a very complicated past, and as we gather more details, our perception of these characters shifts significantly. Baoshu seems like a grim, vindictive stalker, preventing Meijun from moving on with her life. But Meijun, it seems, came to the city to run away from some of the worst, most indefensible parts of herself, things of which Baoshu is an unwilling reminder. For his part, he is a broken man, but hardly a saint, as his violent behavior makes clear. While orchestrated as a subdued melodrama, The Sun Rises exhibits shades of noir, in the sense that everyone is compromised, the weight of the past is inescapable, and no one gets away clean.

Chinese director Cai Shangjun is probably best known for his second feature, People Mountain People Sea, which, like his latest, competed for the Golden Lion in Venice. That film was a revenge story, whereas The Sun Shines on Us All offers a glimpse of a world well past the point of settling scores. One could make a fair argument that Cai’s latest is a deep dive into miserablism, a pitiless gaze at three people whose bad choices are quickly coming to an ugly fruition. But there’s something else at work in The Sun Shines that maybe has to do with the current state of Chinese cinema. The film emphasizes a kind of misguided agency, its characters reacting to trying circumstances in cowardly ways. But as we see throughout the film, this benighted love triangle is happening against a hostile, ruined landscape. The larger environment of Guangdong province is a venal, dog-eat-dog universe in which everyone is angry and embittered, rationality has evaporated, and rapacious gangster capitalism has turned ordinary people into cornered animals. In this context, honor is a fool’s game, and trying to do the right thing only makes you an easy mark.

Watching The Sun Shines on Us All, one is reminded a bit of Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation. The films don’t share much in the way of tone: Farhadi’s film has an Ibsenesque literary precision, where Cai seems more comfortable with muted melodrama. But what unites these two films is the delicate way their directors thread the needle of state censorship and authoritarian oversight. Both films are chamber pieces focused on a small group of people experiencing struggles in their private lives, ones that spill out onto the body politic. And in both cases, the directors slowly reveal to us just how flawed their characters are, leading to a sense of plausible deniability. In Cai’s film, China, like Iran, is not an oppressive hellhole; these are just people who chose badly in their own lives.

But of course, both films clearly display the extent to which these people were constrained by desperation, social mores, and political indifference. The Sun Rises on Us All sidesteps miserabilism by asking us to sympathize with imperfect people trying to make their way in a society that appears irreparably broken. Any noble deed is actually just penance for some earlier misdeed. In the final scene, Baoshu goes to the bus station to try to go back to the countryside, finally leaving Meijun in peace. But there is no goodbye, no reconciliation, just the sudden eruption of the violence that has been simmering under the surface throughout. In the end, the tragedy of two people is mere background noise, as dozens of young people offboard the bus in Guangzhou, new blood for the 21st century Moloch. — MICHAEL SICINSKI

Dry Leaf

“Seeking to reduce a filmmaker’s chief thematic preoccupation is usually a waste of time, for any one worth their stuff works in a storm of competing and converging interests that, if they’re lucky, alights on the ground every few years in a distinct, feature-length form. Alexandre Koberidze, whose third feature, Dry Leaf, premiered at this year’s Locarno Film Festival, is no different. Since his feature debut in 2017, he’s established himself as a leader in a loosely articulated Georgian New Wave, whose characters are caught up in, and asked to navigate, the shifting ground of their national identity, modernity, tradition, progress, regress, and romance…” [Previously Published Full Review.] — CHRIS CASSINGHAM

The Blue Trail

Living in Brazil in a post-Bolsonaro world clearly feels dystopian to director Gabriel Mascaro, who has now made two consecutive films about a near-future where the country’s new rules and regulations take a few cues from a certain Terry Gilliam film with an appropriate title. Divine Love (2019) found an all-encompassing form of state-sponsored evangelical Christianity intermingling with encouragement of polyamorous sexual permissiveness, in the hopes of encouraging more procreation. His new film, The Blue Trail, focuses on how capitalism views the elderly, with anyone over a certain age sent to “the Colony,” a settlement about which nobody really knows anything and from which no one returns. (There’s a minor sort of irony in this film being made under the reign of Brazil’s oldest-ever President, who’d have been sent to the Colony before winning his third term.)

Tereza (Denise Weinberg) is a 77-year old who finds herself thinking about her limited time remaining when the age for Colony eligibility is lowered from 80 to 75, and the signs start adding up. She narrowly dodges being carted off by the police in “the Wrinkle Wagon,” and social workers add laurels to her house in a celebration of her age that also plays like the flipside to the Biblical story about Moses smearing lamb’s blood on the door as a signal to keep away the angel of death. She’s an independent individual who had no plans to retire from her work at an alligator slaughterhouse until she hit 80, but with her unsympathetic daughter assuming custody and not being the type to let her have fun, she decides her ultimate bucket list item is to finally fly in an airplane, and she has to make her way through the Amazon via an illicit boat ride to do it away from prying eyes. It’s The African Queen for contemporary Brazil, but Rodrigo Santoro’s boat captain is more into the psychedelic snail secretions that inspire the title than Bogart’s boozehounding.

Mascaro films tend to be the kind built around a definitive visual, usually sexual: two people having sex on a giant pile of coconuts in August Winds (2014), the sight of an orgy under Christian neon lights in Divine Love, and the titular Neon Bull (2015) in his most successful film to date. Tereza’s age forces him to shift his focus a bit, and the sights here are closer to some of his past work as a documentarian: a giant pile of discarded tires that only exist from the rainforest’s rubber trees being harvested to death, a floating casino on boats, and the odd design of electronic Bibles from a saleswoman who Tereza develops a homoerotic friendship with later on in her journey. The Blue Trail is less than 90 minutes and makes its way through its low-stakes journey fairly quickly, but that’s to its benefit: it’s a short story about a woman’s minor late-in-life epiphanies and finding herself, and it keeps things moving at a sprightly pace that conveys how quickly one has to wrap things up when the end is in sight. The part where Tereza eventually tries the psychedelic snail trail and her eyes turn blue lets Mascaro combine the lights of the floating casino and Memo Guerra’s pulsing electronic score with the sight of two fish. Their fan-like cascading fins and a fondness for locking mouths in a way that resembles both a fight and a kiss surpasses the need for any dialogue, and the film has the good sense to wrap itself up shortly after on a surprisingly melancholy note: Tereza may have found herself, but her days are still rapidly waning and the blue trail will come to an end soon. — ANDREW REICHEL

Amoeba

“I wonder if it’s like being inside an aquarium,” remarks sixteen-year-old Choo Xin Yu (Ranice Tay) as she sits for her Ordinary Level examinations. Facing the examiner, and with a picture of Singapore’s central business district on her desk, she appraises the future laid out before her: the mythical Merlion, a lion’s head atop a piscine body, bestrides the frame, its repose inscrutable. An invention by a British ichthyologist to boost tourist numbers, the Merlion stands tall and proud as the country’s mascot, a silent spokesperson for happiness, prosperity, and progress; at least, this is what Choo’s friends recite to the examiner, what they’re ostensibly expected to do. But something within her resists doing the same. It’s a rebellious streak, to be sure, with her face caught between a scowl and a sneer. It’s also something less recognizable, even to herself, when she catches herself pouring her heart out in a moment of brief catharsis she knows won’t lead anywhere.

Such is the penultimate sequence of Amoeba, Siyou Tan’s perceptive feature debut about the quest for girlhood in Singapore, that it brings into focus the latent frustrations and impulses underlying much of the film. When Choo, maladjusted to the harsh strictures of her all-girls secondary school, is placed into a new class, she finds kindred company in a trio of similarly insubordinate teens who fall for her publicly insouciant attitude. With Vanessa (Nicole Lee Wen), Sofia (Lim Shi-An), and Gina (Genevieve Tan) she obtains some respite from her stern teachers, who peddle Confucian truisms and punish the slightest clothing infraction; when Sofia takes them all to meet her family driver, Phoon (Jack Kao), he playfully suggests that they form a gang to consecrate their friendship. How different, after all, are the gangster’s tenets of loyalty and brotherhood from those of “excellence, duty, and honor” sermonized by the school?

This question nonetheless articulates the thorny phenomenon, so central to Amoeba, of a generation of youth grappling with who they are. Gone are the days of rampant hooliganism, and the film’s representations of contemporary middle-class Singapore are worlds away from the unruly reality of juvenile delinquents in Royston Tan’s seminal gangster movie 15 (2003). Where Choo and her friends are concerned, rule-breaking and acting out are meek attempts to clear the stifling air — exacerbated by an institutionalized conformity muting creative expression and constraining individuality. And though the rituals of teenage sisterhood and camaraderie constitute a pretend play the girls will inevitably outgrow, they are to them necessary delusions, part and parcel of formative selfhood: growing up, falling in love, falling out of love, and growing up some more.

Amoeba’s sensitive portrait of a restless coming of age renders its characters with no little verisimilitude, but its realist strokes, intriguingly, are bookended by a foray into the supernatural. Confiding in her friends about a ghost haunting her bedroom, Choo borrows a camcorder from Sofia to catch it on film; the elusive presence, however, unwittingly brings to the surface other undercurrents not mentioned, much less tolerated, by the prim and polite society around her. Though Tan has clarified the literalness of her ghost, the latter’s symbolic import as a return of the repressed isn’t precluded amid the violently practical order of the day. What cannot be seen is not real, just as what isn’t acknowledged cannot pose a threat. Desire, queer or otherwise, circumscribes itself within a layered and hierarchical nexus of race, class, and gender; to act otherwise — in short, not as the model Chinese daughters of an elite workforce — would be to fail the system and, as one teacher decries, become “ungovernable.”

Yet the absence of government is neither palpably apparent nor wholly liberating for the girls, who swear an oath, get into trouble, and end up in the same exam room, waiting to close a chapter in their lives. The paradox at the heart of Amoeba lies in its shape-shifting titular metaphor: an island of the individual, a tabula rasa in search of the external world. Both fiercely independent and craving an identity wrought in the shadow of others, Choo, Vanessa, Sofia, and Gina cosplay as swaggering cool kids, a twinge of self-awareness burrowed into their happy naïveté. They question authority, doubt history, and challenge the sanitized narratives of life and success as are fed them. They wonder to themselves whether sincerity alone can cut it with the powers that be. Retreating into a cave beside their school, they purge themselves of the codes of conduct, if only fleetingly, and enact new ones among the soon-to-be-excavated relics of a previous century. “Emptiness is the body,” intones Choo in labored, visceral prayer, keen to exorcise the ghost in her room. With an intensely personal eye, Amoeba composes out of this emptiness a defiant and staggeringly vulnerable tale of adolescence found, lost, and regained once more. — MORRIS YANG

It Was Just an Accident

“Despite its almost apologetic title, the latest feature from Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi bears a highly incendiary load. Not quite a call to arms against the raging of tyranny as much as a film that unflinchingly wrestles with the moral dilemmas this tyranny engenders, It Was Just an Accident finds the long-time dissident against Iran’s Islamist regime working in a more explicit and even openly defiant register compared to his previous works. Having been imprisoned twice and slapped with an ongoing filmmaking ban, Panahi is no stranger to the paranoia he dramatizes so vividly in the film’s setup…” [Previously Published Full Review.] — MORRIS YANG

Meadowlarks

Tasha Hubbard’s debut fiction work is a clear-eyed, frustrating compound of incomplete scenes and rounded emotional resonance, where characters speak in terms defined either by stilted exposition or historical exorcism. It’s quite early on that Meadowlarks defines its terms, where in a brief conversation between four estranged siblings — coming together in Banff for the first time since their forced separation during the ‘60s Scoop — it’s underlined that the translation of their family name, Wasepscan, renders out to the titular songbird. Naturally unfurling from this point are discourses on family, the violences of colonial intervention, and the alienation inherent in the dissociation from one’s culture: the existential vacuum that bleeds the absence of language, ceremony, and understanding. Hubbard doesn’t quite manage to cohere all of these pieces into a total work, fussily cutting to and fro between scenes that take on the role of structural mediator between more fleshed-out expressions of interpersonal reconciliation.

It’s not difficult to discern this either, for so many of these moments are curt and far too concise to hold the weight of their dramaturgy. It’s jarring to push through a less than two-minute articulation of unrest and into a near ten-minute group share of personal histories and familial strife. This dramatic amorphousness is further implicated by a visual language with a rudimentary decoupage that proffers no insight into any single circumstance, any single character, or any single dynamic: everything is both immediately legible and spelled out in explicit pronouncement across the entire runtime. Apart from a single scene where the family is invited to sit down with a local Indigenous couple and their son — a scene that itself is still plagued by the languishing syntax of coverage, with the only semblance of an animated soul existing in its insistence for direct address of both a settler-colonial history and its traumas — there’s little else that manages persist past the film’s shortcomings.

A cinematic inertness hampers the film’s capacity to carry its narration, but it would also be unfair to reject outright the stirring confrontation that grounds its haphazard formalism. But even then, the project’s screenplay seems aloof to its own representation of the relationship dynamics within this family. Beyond what’s been touched upon above, there’s a single aspect regarding the fifth sibling — the eldest, most discomforted, whose capacity to recollect the scoops as they occurred situates him in an isolation rooted in experience — where his refusal to join this reunion introduces a complication to the processes of reckoning, a thread which would have undoubtedly proved effectual than much of the pointed exposition. This presence — and absence — understandably caught in the periphery, should have been a more substantial part of the whole, and its wedged-in position is indicative of much of the work’s more contrived register.

Of course, to some degree these ailments are a product of the difficulty in adapting a documentary to fiction, where the expected structure of classical narrativity is enforced onto a story that is anything but amenable to these constrictions. This decades-spanning tale of forced separation, from both family and culture — the consequential, bureaucratic amalgamation of hundreds of years worth of settler-colonial oppression and dispossession — cannot be represented through the structures that helped to ideologically affirm these very acts of violence. While it is understood that this is not the response many will have to these narratives being finally represented, regardless, their representation here doesn’t quite break free of the colonial gaze that harbours itself through these classical formalisms. Such a cinema is already out there, and it will take the continued praxis of deindustrialization, on both a personal and systemic level, to remove this yoke where the imagination is latched onto colonial hegemony. — ZACHARY GOLDKIND

Olmo

Mexican director Fernando Eimbcke is a delight, a playful formalist in a sea of self-serious festival auteurs. But because comedy is often viewed askance by the Powers That Be in world cinema, Eimbcke is frequently overlooked in favor of more serious filmmakers. He could be compared to Argentina’s Martín Rejtman, perhaps, although Rejtman’s films are much drier than Eimbcke’s, which are also a bit more openly sentimental. There’s a roughness, a handcrafted quality, to Eimbcke’s films, like Wes Anderson in comfortable shoes.

But his fourth feature Olmo may gain a bit more traction than his last three, Duck Season (2004), Lake Tahoe (2008), and Club Sandwich (2013). This one has backing from Teorema, the production house of current Mexican cinema poster boy Michel Franco, and Brad Pitt gets an executive producer credit. It’s also set in New Mexico and is about half in English. If Eimbcke has a big break coming to him, Olmo is very likely the film that’ll do it. It’s a wry family comedy centered on 13-year-old Olmo (Aivan Uttapa), who we first meet jerking off in his bedroom. This rosy-palmed reverie is interrupted by his father (Gustavo Sánchez Parra) calling to him from the next room. This, in a nutshell, is the central crisis at the heart of the film.

Olmo’s dad Nestor is infirm. He needs constant care, because he cannot walk, sit up, eat, or go to the bathroom by himself. (Near the end of the film, we learn that Nestor suffers from multiple sclerosis.) Olmo’s mom (Andrea Suarez Paz) is unexpectedly called into work, and older sister Ana (Rosa Armendariz) has plans at the skating rink. So Olmo is forced to stay home and care for Dad, even though he and his friend Miguel (Diego Olmedo) want to go to a party with Nina (Melanie Frometa), the hot girl across the street. (Olmo was imagining her washing the car in a bikini while pleasuring himself. This is serious.)

It’s 1979. Phones have long curly cords. Stereos have turntables and cassette decks. TVs have rabbit ears. There’s disco. And Olmo abides by the genre rules of the classic late ‘70s/early ‘80s coming-of-age film. Of course, Olmo and Miguel break the rules and leave Dad alone to go try and score. Much of what Eimbcke has to offer you’ve seen before, although perhaps with less symmetry or precision. But there’s a melancholy undercurrent here that suggests that Olmo is as much a story of Nestor facing his own mortality as it is Olmo trying to become a man.

Olmo’s story is indeed the focal point of the film, but it’s also very much about Nestor and how his family copes (or doesn’t) with his illness. His wife, we discover, takes as much work as possible, not just because they need the money, but also to get out of the house. Ana openly defies Nestor by smoking in the house. And when Olmo spills soup in Nestor’s shirt and is trying to help him change, he gets frustrated and asks, “what difference does it make? Why do you bother to get dressed at all?” It’s easy to find all of this very affecting, and not just if, like this writer, it mirrors one’s own family experience with helping a handicapped member. Eimbcke and Sánchez clearly display the loneliness and wounded pride of a man who, through no fault of his own, cannot care for himself. He just wants his place in the family he helped create, and continually finds himself sidelined.

Near the conclusion of Olmo, Eimbcke borrows a technique from Ramon Zürcher, providing a kind of recap of the film’s narrative by providing still shots of props and objects that have appeared throughout the film: a wet mattress, a junk car, the old stereo, etc. This formal tactic helps mitigate the overt sentiment that holds the film together, reminding us that there is an objective world that all of us are constantly trying to navigate. Olmo is young, and cannot yet help seeing others as objects: Nina being a sexual goal and Nestor an impediment to that goal. By focusing our attention on actual things, Olmo helps us see the kid’s partial exit from youth’s essential egocentrism, as he learns what it means to show up for others. — MICHAEL SICINSKI

Dandelion’s Odyssey

“Biblical scholars and theologians use “antediluvian” to describe the world of Genesis between the fall from Eden and the flood. Literally meaning “before the flood,” the word packs grand meta-narratives of historical and cosmological significance: humans fumbled the chance to live in paradise for good and brought down our world with it. Disaster awaits, monsters lurk. The beauty of the original creation still radiates brightly in the meantime. This is the world that Momoko Seto’s Dandelion’s Odyssey drops into…” [Previously Published Full Review.] — JOSHUA POLANSKI

Comments are closed.