Blue Heron

Sophy Romvari has used cinema to mine the fractured, seemingly incomplete nature of her family history since her first short film, Nine Behind. In that film and others, whatever pieces of physical archive might elude her, she makes up for in a rigorous but soulful exploration of the archive of memory, so stories and artifacts compete and merge to form an imperfect picture.

Now, after nearly a decade of short films under her belt, Romvari finally debuts a feature, Blue Heron, that advances her approach to reconstructing, confronting, and reconciling the gaps in her, and her family’s, story — albeit this time in a fictional context. Set in the late 1990s, it follows a Canadian-Hungarian family’s uneasy move to Vancouver Island, during which the parents struggle to deal with their eldest son, Jeremy’s (Edik Beddoes), increasingly worrisome behavior.

Formed mostly through the eyes of the family’s youngest daughter, Sasha (Eylul Guven), our impression of Jeremy is not one of strained pathology, but constant empathy. Sasha’s curious gaze is often mediated — by closed doors, windows, physical distance, emotional maturity, or the lens of a video camera — though her perspective never feels wanting. In fact, the distance of Romvari’s camera, at once admiring and wary, is a meaningful way to observe this troubled family, for the film’s strengths lie in implication and ellipsis, not in explication. Jeremy may not be the father’s biological son, he may or may not have tried to end his life by cutting himself, and he may be beyond “saving,” but Romvari never deigns to instruct the viewer. Instead, what Romvari prizes is the bond — borne out of silent emotional and gestural exchanges — between Sasha and Jeremy.

Their bond is in sharp relief to Jeremy’s relationship to his mother and father. The silence between them festers with low-level threat such that even fleeting moments of peaceful release and shared joy — one evening the whole family engages in solitary artistic pursuits that become communal — nevertheless twinge with unspoken tension. The mother and father’s desire for a diagnosis of Jeremy’s condition is the human need for closure. Therapists and counselors struggle to fulfill that need, offering assessments that are ultimately incomplete and unhelpful, so the distance between them grows to a seemingly impassable gulf.

Until the halfway point, Blue Heron appears to be a handsomely mounted drama, sharply rendered in thoughtful period detail and moving performances of varying emotional registers. But this is a Sophy Romvari film, so form and style were never likely to be treated in such straightforward ways. Set 20 years in the future, the second half of Blue Heron is full of formal revelations and grace notes that are worth keeping a mystery; but one, which happens during an early scene after this forward temporal leap, is worth elucidating.

At this point in the film, the question of how much of herself Romvari is going to inject into the proceedings starts to scratch underneath the surface. Sasha, now an adult, is a filmmaker who has gathered a group of social workers to discuss a case study for a young man we assume is Jeremy. Amidst a stream of despondent non-answers and partial explanations (“It’s hard to predict… it’s hard to tell”), one miniscule shot, a seemingly insignificant cutaway of a hand turning a camera on its tripod, disrupts the scene’s familiar form. There’s no explicit reference to this little cinematic secret, but there is an illogic to its place within the scene — for it can’t have been done by Sasha — that immediately suggests Romvari’s omnipresence in a brand new way, far beyond her role as a director. It’s the kind of intervention by the filmmaking apparatus itself that has guided Romvari’s practice from the very beginning, and which charges the rest of the film with a quiet, tortured ecstasy that guides it as close to a feeling of closure anyone dealing with the unanswerable could hope for. — CHRIS CASSINGHAM

Sentimental Value

In Sentimental Value, there’s a scene where the veteran filmmaker Gustav Borg, played by Stellan Skarsgård, explains to his newly discovered lead actress, Rachel Kemp, how his mother hanged herself using the very same stool being used. Poor Rachel is overwhelmed by the extreme intimacy with which Borg confides in her about his past. This seemingly trauma-laden relic is later revealed to be a random IKEA stool, when Borg’s young daughter Agnes mentions to him this exchange. One of the many gags that lightens the dramatic flow of Joachim Trier’s Grand Prix–winning film, the stool can be read as an extension of the gap between Trier’s intentions and the mental projections through which the audience engages with the story.

Rather than a main character, as was the case in The Worst Person in the World, it is an old, picturesque family house in Oslo around which the stories of Sentimental Value gravitate — a curious similarity the film shares with another 2025 Cannes Comp title, Mascha Schilinski’s The Sound of Falling, even though both works take markedly different sensory and emotional approaches to spatial memory and generational transmission.

Nora — a stage actress whose name alludes less to some predestined meaning than to Trier’s choice to adorn his film with rather-too-obvious references to Ibsen (and later to Chekhov and even Bergman) — and her younger sister, Agnes, grew up in this house, as we learn from the voiceover narrator. During their childhood, it appears that the girls’ father, Gustav — who inherited the house from his family — left them. Upon their mother’s passing, he casually decides to reconnect with his estranged daughters. Nora is furious, while Agnes just wants to avoid drama.

His daughters are not the only object of Gustav’s reconnection efforts. A veteran filmmaker with no films in the last 15 years, he is preparing for a comeback with a script he wrote with Nora in mind for the lead. Grumpy and dissatisfied to such an extent that his character lends a comedic tone to the film, Skarsgård’s Borg channels more of an oddball Werner Herzog figure than the austerity of a Bergman protagonist. For instance, in a part cringey, part humorous moment, he gifts The Piano Teacher and Irreversible to his grandson.

Renate Reinsve, whose Nora is constantly at odds with her career-driven, irresponsible father, isn’t really given the chance to deepen her character. After a chaotic, whirlwind opening sequence — where the “hot mess” act before an important premiere makes it feel like she hasn’t quite shaken off Julie, her character from The Worst Person in the World — she mostly engages in a series of passive-aggressive confrontations with her father, in which things keep being left unsaid.

After Nora’s initial rejection, Gustav tries his luck with the aforementioned American actress Rachel Kemp, whom he meets at a film festival — possibly Deauville. Even though her character is meant to embody the zealous and superficial American star, Elle Fanning delivers a surprisingly charming and heartfelt performance. She’s written to be sincere in an irritating way, and Fanning nails it — especially in the scenes where she clumsily tries to unearth Gustav’s past, and that of his mother, in her slightly invasive attempts to fully grasp the ethos of her role.

In Sentimental Value, Trier returns to the dysfunctional family dynamics he previously explored in Louder Than Bombs. Within the narrative economy of the film, the relationships between Gustav, Nora, Agnes, Gustav’s late mother in absentia, and even Rachel — who functions as a stand-in for Nora — gradually come to resemble a web of loosely woven threads, culminating in a predictable outcome in which art and cinema serve as the sublimation of trauma and as a path toward healing and reconciliation — an ending whose prosaism and familiarity are less problematic in themselves than the apparent lack of stylistic and formal consideration brought to the use of the cinematic medium in expressing them.

It’s beyond doubt that Joachim Trier is, a priori, a cinephile filmmaker, and his cinema has always been imbued with an array of influences, homages, and reworkings — as if the images themselves were inhabited by other cinematic visions. Inhabiting the image — Trier would often frame his spaces with such evocative power that, even long after the film had ended, one could still mentally visualize and feel the characters lingering in their habitus, as if they were latent images. It’s precisely this kind of sensory aftereffect that Sentimental Value seems to lack — at least on the surface. The Borg family mansion merely resembles an artificial studio set piece, shot with the sterile detachment of an Architectural Digest video ad. Is this truly the house meant to represent the memory-laden, regretful past that Nora cannot let go of and that Gustav tentatively revisits? Are we meant to believe in the authenticity of the attachment these characters seek — in one another and in the past? Or could Trier, in fact, be intentionally employing this flatness and sense of uprootedness to convey the unbridgeable gap that separates father and daughter, and their respective understandings of love and life?

Sentimental Value is either an emotionally disproportionate, tone-deaf dramedy, or an ambiguous and intelligent meta-text that playfully and persistently gestures toward the very “sentimental value” the audience is meant to seek within it. A malleable piece of work, the film echoes the dual suggestiveness of that IKEA stool Gustav jokes about — a curious quality that may be the one and only virtue by which the film will be remembered. — ÖYKÜ SOFUOĞLU

Mare’s Nest

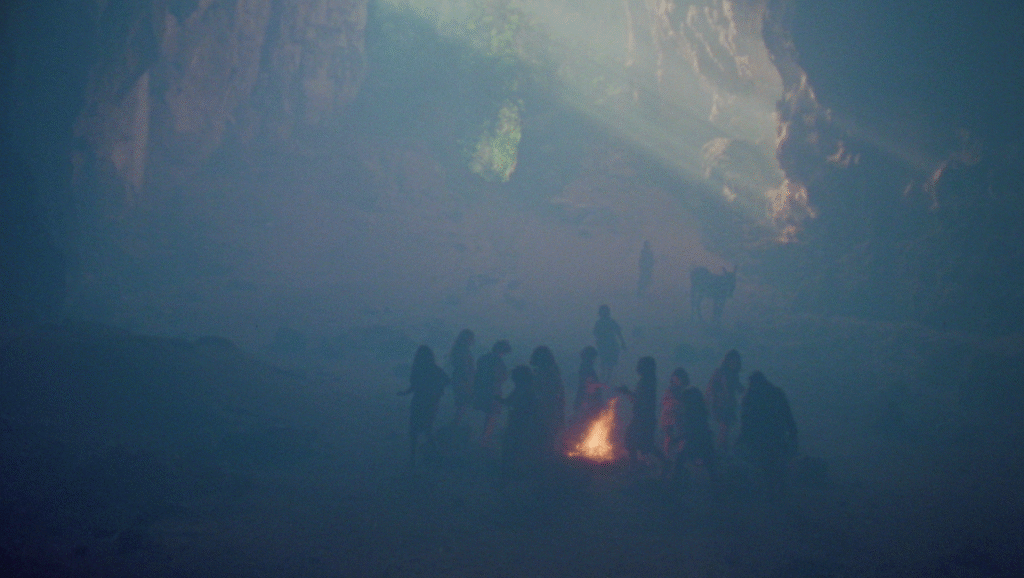

If the end of the world left the children in charge, what kind of future might they build? This question simmers underneath a surface of experimentation and fable in Ben Rivers’ latest feature, Mare’s Nest. Divided into chapters with names like, “Anarchy,” “The Word For Snow,” “Moon Meets a Community,” and “Ah, Liberty!”, the film follows a young girl, Moon (Moon Guo Barker), as she wanders the rocky outcrops of an unnamed island (the film was shot, in part, on the island of Menorca); converses with an ancient scholar and her translator (in an adaptation of the Don DeLillo play, The Word For Snow); and encounters other children who have formed an improvised but peaceful community, in a bid to find answers to what happened to the post-apocalyptic world around her.

The effect of Moon’s wanderings is a feeling of uncertainty bolstered by youthful optimism. She is a curious child, more often determined to find answers where seemingly there are none and continue unabated when one avenue of inquiry turns into a dead end, than to sink into resignation. Moon’s buoyancy is a useful counterbalance to the feeling of accumulative dread about the illogic of the present day that Rivers has said inspired Mare’s Nest. Indicative of the unreality of the present day, one scene shows Moon coming across an abandoned tunnel where adults are frozen in grotesque, borderline baroque poses, like the famous lovers of Pompeii, though without the pang of curtailed romance. The inclusion of the DeLillo play from 2007, written in response to the ongoing but largely ignored global climate crisis, also makes sense. The play’s grim intonations, voiced by two child actors playing The Scholar (Astrid Ihora) and The Translator (Elahni-Ja’nai Nembhard), that “the world is an open wound,” and “this is what will remain… the names in your head,” ultimately fall to Rivers’ more hopeful but open-ended ideas about freedom and exploration.

The community of children Moon takes up with briefly isn’t a straightforward antidote, either. Their peaceful tranquility is carried on an air of complacency. Their games of chess with found objects, their bonfire dances, even their improbably homemade movies, suggest a clan of people satisfied by their own self-sufficiency. But Mare’s Nest is not a film that envisions complacency in any direction, either towards the cynicism of The Translator or the insulation of the community of children. As a title, Mare’s Nest does double duty, indicating toward a constant stream of illusions — one remarkable scene depicts the screening of a film, seemingly of their the children’s own creation, about a minotaur that accidentally kills one of their own and is banished to a rock labyrinth from which it can’t escape — and to post-apocalyptic chaos. Answers to the world’s illusions and chaos are elusive, but what Moon’s experiences lack in explicative material, they make up for in signifiers and ritual. A young boy plays his keyboard behind an old caravan like a little folk hero, while another reigns over a scrapyard, listening, inexplicably, to “Too Many Questions” by Frustration on a disused car’s radio.

There’s a delightful, handmade quality to Mare’s Nest. The beautiful texture of the super-16mm film gives life to the similarly handmade objects in the isolated worlds Rivers and his young collaborators invented. A hand- (or foot-) powered film projector, a chess board of found objects, a string instrument made of old bicycles. In any other film, they would probably feel like cloying attempts at whimsy. Here, they’re the unconventional outcrops of a life lived on the margins. It’s no surprise, then, that Mare’s Nest never really resembles the post-apocalyptic doom found in most other cinema, nor the primal energy of Lord of the Flies. There is a confluence of pleasure and frustration as the dense content of the film’s source materials — among them Fernando Pessoa’s The Mariner and OOL by Daisy Hildyard — find their place in its lively, experimental verve. For all the attention and surrender it sometimes demands of the viewer, there is pleasure in simply being offered the challenge. — CHRIS CASSINGHAM

It Was Just an Accident

Despite its almost apologetic title, the latest feature from Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi bears a highly incendiary load. Not quite a call to arms against the raging of tyranny as much as a film that unflinchingly wrestles with the moral dilemmas this tyranny engenders, It Was Just an Accident finds the long-time dissident against Iran’s Islamist regime working in a more explicit and even openly defiant register compared to his previous works. Having been imprisoned twice and slapped with an ongoing filmmaking ban, Panahi is no stranger to the paranoia he dramatizes so vividly in the film’s setup: a vehicular breakdown prompting family man Rashid (Ebrahim Azizi) to stop by a mechanic whose assistant, Vahid (Vahid Mobasseri), recognizes him as his captor and torturer. But Rashid, or Eqbal the “Peg Leg,” is, for the most part, contrite if insistent on his innocence, when he isn’t kept comatose and locked up in the back of Vahid’s van. His discovery and detention were accidental; what to do with him is a matter of serious and difficult deliberation.

Equal parts thriller and political drama, It Was Just an Accident potently documents the travails of retributive justice. Its influences may be literary, such as when the hesitation underpinning its extrajudicial process is compared to Beckett’s Godot, and the film’s characters may, to its detractors, be reduced to ideological conduits. Yet Panahi’s urgency and realism shine through his metaphysical terrain of good and evil. When Vahid informs his friend and erstwhile regime victim Salar (Georges Hashemzadeh) about his intention to off Rashid, Salar urges grace while directing the vengeful man towards Shiva (Maryam Afshari), a wedding photographer midway through a shoot with bride Golrokh (Hadis Pakbaten) and groom Ali (Majid Panahi). Both women were personally tortured by the Peg Leg, and both are torn between denying the dredging up of this painful past and determining Rashid’s identity beyond earthly doubt. Shiva’s ex-boyfriend, the impulsive and utterly furious Hamid (Mohamad Ali Elyasmehr), is also enlisted, making Vahid look positively stoic in comparison and threatening to derail the stab at due process that would arbitrate between righteous killing and wrongful martyrdom.

Neither legality nor even ambiguity, however, informs the film’s crux — and though the hip logorrhea of Anatomy of a Fall might have entranced many, Panahi’s precepts are simpler but consequently more terrifying. On the surface, powerful in its own right, It Was Just an Accident paints a staid if affecting portrait of vigilantism, its fantastical catharsis deflated in the moment of absolute agency. At a deeper and more unnerving level, the contingency of its narrative enterprise provides a radical critique of this agency. The God that Rashid unsuccessfully assuages his young daughter with at the film’s start sets nothing in stone, and His fickleness in precipitating the civilians’ wild goose chase for truth and closure pits both objectives, on occasion, against each other. The open wounds that a reign of terror perpetuates, nonetheless, necessarily remain open: where the film’s penultimate sequence, a confessional tour de force, offers some much-needed reprieve, its chilling final shot might have just foreclosed it indefinitely. Sparse, naked, and blistering, It Was Just an Accident may be Panahi’s most invigorating film yet. — MORRIS YANG

Ancestral Visions of the Future

“An ode to cinema” — an audacious claim with which to open one’s feature, but audacity courses through the work of Mosotho filmmaker Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese. He’s as qualified as any contemporary director to characterize his film as such, an artist to whom future cinematic odes may justly be dedicated. His 2019 narrative feature This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection radiated a kind of creative passion and vitality that could scarcely be believed given the modesty of its production. With the international acclaim it received, he’s boldly chosen to narrow his scope with his follow-up, turning in on himself for the esoteric, quasi-autobiographical Ancestral Visions of the Future. A vivid, personal juxtaposition of visual essay and verbal poem, its stylistic celebration of the audiovisual arts ensures its worthiness of the aforementioned claim, even if Mosese’s commitment to the eccentricities of his premise prevents it from achieving a power equal to his previous feature.

Mosese tells of his childhood in Lesotho, moving between towns, homes, and familial guardians, and then his adulthood in Berlin, in a florid voiceover whose poetic indulgences are capable of captivating and enervating in equal measure. His romantic vocabulary is overly dense, but also beautiful and richly descriptive; the film has no diegetic dialogue beyond occasional clips of documentary footage, seamlessly spliced into enacted sequences that accompany the narration, and for all its overbearing verbosity, it tells Mosese’s story with potency and sincerity. But he’s a lesser wordsmith than he is an imagemaker — in a time when blockbuster films largely appear awash in grey sludge, and drab palettes and shallow depth of field define the aesthetics of so many independent films, Mosese’s films are vibrant in color and detail, and the full emotive and narrative capacity of the cinematic image. His textures are palpable, his spaces alive with character, his colours exquisitely saturated. Ancestral Visions is too authentic in its style to be quite hyper-real, even in its Parajanov-esque expressive tableaux, yet never visually dull. The combination of the wondrous cinematography, courtesy of Phillip Leteka and Mosese himself, with the soundtrack of voiceover and Diego Noguera’s anxious, atonal score and sound design, produces a most singular artistic statement, communicating the tenderness of Mosese’s recollections — the romanticized nostalgia and the clear-eyed pain and regret.

These recollections concern the past but are related in the present, in a film whose very title blurs distinctions between temporal states. We live for the future, but can never escape the past — by the time information has reached our sensory organs, been transmitted to the brain, and translated into knowledge and appreciation of the world around us, it’s already in the past. Mosese’s memories are thus depicted as a past (in his voiceover) still present (in the images [re]created). He tells of his mother’s toil, envisioning a future for her family, one that both has now faded into memory and is still occurring. He tells of the rural communities that abandoned their villages for a future in the city, where the violence of encroaching poverty was replaced by the threat of physical violence, and the violence of the fear this instilled. Ancestral Visions operates in a temporal zone in which the future of the past and the past of the future co-exist, experienced, described, remembered, foreseen, and known concurrently. This is the film’s most compelling quality, a relationship to time that recalls Resnais in its implicit assertion that all one’s previous experiences are not lost to time, but rather accrue as they occur and recur ad infinitum until death. The pain of the past is never forgotten, but then nor is the joy.

If this provokes some academic interest, it’s of limited efficacy — it’s somewhat incidental, as Mosese’s preoccupation appears to be telling his story, and he does so by sacrificing a little insight and candor for grandiosity. In his magnificent images, he indubitably earns his flowers for this sacrifice, but the narration that ties these images together is too turgid, too loquacious to connect with the viewer. The artistry is plain to see and easy to appreciate, and the academic interest is obvious, but Ancestral Visions’ virtues don’t extend far beyond these attributes. It’s nonetheless a fine, unique film with enormous value in some aspects, but it demands a few more aspects to make the impression it should. — PADAÍ Ó MAOLCHALANN

Comments are closed.